VERA'S VOICE

|

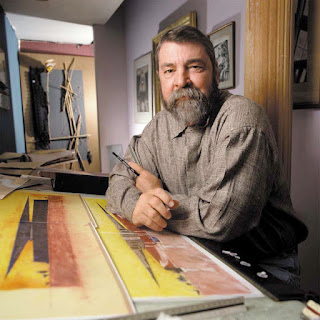

| Vera Hall. 1959. Photo by Alan Lomax. Courtesy Alan Lomax Ar |

By THOMAS SPENCER

News staff writer

February 6, 2005

ON THE NET www.verahallproject.com

Since 1964, the body of Vera Hall, an impoverished black cook and cleaning woman, has rested forgotten in an unmarked grave in Livingston.

But in 1999, her legendary voice - sweet and sorrowful - rose 'round the globe in a spiritual groan out of Black Belt cotton fields, but now set to a throbbing techno-beat. The single, dubbed ''Natural Blues'' on DJpop star Moby's multi-platinum album ''Play,'' entranced patrons of rave clubs in international capitals, revived interest in Hall and generated what should have been a large stream of royalties.

But the question of who received those royalties is clouded. Flowing through record companies, publishers and agents, Hall's share eventually trickled down to a white Tuscaloosa woman. The white woman's daughter says her mother cared for Hall, who was nearly blind from cataracts. Out of gratitude and friendship, Hall willed her the royalties, which had never amounted to much.

But relatives insist Hall wouldn't have cut off her great-grandson, whom she adored. Now a hospital worker in Tallasee, he feels robbed of an inheritance rightfully his.

And Hall's grave remains lost and unmarked.

The saga makes all the more haunting Hall's ''Trouble So Hard,'' the recording used by Moby. In it, Hall sings in a stark a capella:

''Oh Lordy, trouble so hard, Oh Lordy, trouble so hard. Don't

nobody know my troubles but God. Don't nobody know my troubles but God.''

Born in rural Sumter County in about 1905, Vera Hall ''has the loveliest untrained voice I have ever recorded,'' wrote the ethnomusicologist John Lomax, who scoured the South, beginning in the 1930s, preserving the work of folk and blues singers. Her talent compared to famous Lomax finds like Leadbelly, Jelly Roll Morton, Mississippi John Hurt or Robert Johnson.

After Lomax's visit in the late 1930s, Hall received visits from other folklorists, professors, writers and poets who were drawn by her voice and her enormous repertoire of spirituals and folk songs. Lomax returned several times and, at the invitation of John Lomax's son, Alan, who carried on his father's work, Hall performed in a 1948 Columbia University concert in New York City, sharing the stage with Pete Seeger.

But Hall, a pillar of her church and secretive about her love of secular blues, never pursued a music career, instead working quietly as a nursemaid, cook and cleaning woman for white families in Sumter County and, later, in Tuscaloosa.

''Gracious, gentle, and caring,'' Hall's manners are ''so serene and so gentle that she quickly puts one at ease,'' Alan Lomax wrote. Though a ''nice, Christian-like lady,'' she enjoyed drinking with friends and carousing.

Her speaking voice, captured on recordings, has a warm, polite elegance. And she somehow kept an optimistic disposition despite a life of tragedy. She lost both parents and her sister. Her husband, a coal miner, was murdered by another miner. Her daughter died at 20. Her two grandsons, whom she helped raise, both died in their 20s. All of that before Hall died at 58.

Calling across decades

She had been virtually forgotten in the state of Alabama.

But the Moby song changed all that.

When he first heard it on his car radio, something about Hall's voice haunted Gabriel Greenberg, a Vermont teenager. ''I remember being totally transfixed with that track,'' Greenberg said.

It seemed Hall was calling him from somewhere far away, across

decades and racial divides. When Greenberg went to Yale University, his curiosity about Hall bloomed into an obsession and a major research project, the result of which is The Vera Hall Project, a comprehensive biographical Web site, www.verahallproject.com, dedicated to Hall.

Plying backroads in his Honda Accord during the summer of 2002, Greenberg poked around cemeteries, interviewed elderly black residents and attended their church services.

Greenberg's attention and the material he produced helped the cause of University of West Alabama professors Alan Brown and Tina Jones, who'd been campaigning to get Hall inducted into the Alabama's Women's Hall of Fame. This fall, Hall was voted into the Hall of Fame, and she'll be inducted in the summer.

Alan Brown said her induction is especially sweet, seeing as she passed much of her life as ''one of those invisibles.''

''She gives a face to all the anonymous folk singers in our state that passed down this great legacy of folk singing,'' Brown said. ''That one of them got in the Hall of Fame stands for all the others that passed away forgotten.''

LeBlanc's quest

Hearing Hall on Moby's recording set Patrick LeBlanc on a quest, too. LeBlanc, a Mississippi blues fan, has made a career out of locating lost blues artists and pursuing royalties on their behalf. His company is paid out of found money. Recently, LeBlanc and his company, Mighty River, were able to track down and get royalties to Willie Jones, who is still alive, when American Express used his music in an ad starring Tiger Woods.

The outcome of LeBlanc's research on Hall ended differently. ''I started digging around and checked the probate court in Alabama. She did have an estate and she left a will and pretty much willed everything to the lady who was taking care of her.''

Hall's will, written in 1961, was signed with an ''X.'' Three sections concern the royalties from Hall's music. The will names Pearl Owen the executrix, charged with paying any outstanding debts and receiving whatever was left.

Pearl Owen is in the advanced stages of Alzheimer's at a Tuscaloosa nursing home. Jan Sikes, her daughter, feels that Hall is reaching out from beyond the grave to help the woman who helped her in her final years.

The Owens operated a store in a working class neighborhood in Tuscaloosa and depended on the black community for business. Hall

lived on the same block as the store.

Sikes said her brother delivered groceries to Hall and shared her cornbread. Pearl Owen helped get Hall's Social Security checks going. Nearly blind from cataracts, Hall depended on Owen to help her with bills and paperwork.

According to Sikes, gratitude led Hall to turn what little she had over to Owen. The recordings had been a source of pride and conversation for Hall, but she'd received only modest and infrequent royalties. Neither Hall nor Owen could have fathomed at the time something like the Moby recording, Sikes said.

When Alan Lomax's daughter, Anna Lomax Wood, heard Moby's album, she began her own search for Hall's heir, contracting with a professional genealogist.

She managed to track down Hall's great-grandson Willie Nixon Moore, who lives in Tuskegee. She then contacted two lawyers on Moore's behalf, but both reported back the same thing. The will couldn't be contested, it had been too long and Owen was legally entitled to the royalties.

Willie Nixon Moore doesn't believe Hall would have disinherited her family. ''Although my grandmother is dead, I'm going to speak for her,'' Moore said. ''I'm going to be her voice. All I want is what is due to me.''

A different tale

The Moores tell a different story of Hall's relationship to the Owens. She could read and write, they say. They say Hall ironed for the Owens and probably bought groceries on credit when times were tight. But Hall remained close to her family, even after her grandson, whom she'd help raise, died in 1955. Hall sang lullabyes to her great-grandson, Willie Nixon Moore, and after he moved with his mother, Ella Mae Moore, to Cincinnati, they returned frequently for visits.

''She read the Bible to me. Her cornbread tasted like cake,'' Moore said.

Moore, who has two boys, 27 and 15, and a step-daughter, said he intends to make another push for a share of the royalties. ''I've been struggling all my life. I'm going to be 50 years old. I work hard and I don't take anything from anybody. Give me a just due. Just recognize me,'' Moore said.

Moore's mother said Hall believed that, one day, her recordings would be worth something. ''She'd say to him, One day boy you are going to be rich.'''

When Hall died, Ella Mae Moore returned to Tuscaloosa and paid Hall's outstanding telephone and gas bills, she said. When the will

was probated, a hearing was held at which Hall's family could have contested the will. But a certified letter and legal notice didn't reach the Moores. The judge finalized the will a few months later.

''It was impossible to fight them, but it was just wrong,'' said Don Fleming, assistant director of the Lomax Archive. ''Legally, she may be entitled to the royalties, but morally, HE certainly is.''

For Gabriel Greenberg, the royalty question is like the odyssey in pursuit of Vera Hall's story.

''It's complicated. It's all about ambiguity,'' Greenberg said.

The Lomaxes profited from the Moby royalties. The way the song was copyrighted, Lomax was effectively the co-writer and publisher as well as the producer of the recording.

Similar arrangements with other artists have resulted in criticism of the Lomaxes. But without them and their promotion of music that at the time was dismissed with contempt, much of it would have been lost. And Vera Hall would have almost certainly passed from the earth remembered only by friends and family.

General industry standards call for royalties to artists of 81/2 cents per unit sold. Moby's album sold about 10 million copies worldwide, thus generating a potential pot of $850,000 in royalties from the song that sampled Hall. Everyone contacted declined to say how much they received, leaving a field of questions, and neither Moby nor his representatives returned calls on the matter.

How much did Moby owe Hall for the use of her voice, the use of a song gifted to her from prior generations? How much should go to John Lomax, who made the original recording and shares credit with Hall on the song?

How much is owed to LeBlanc's Mighty River for pursuing the claim? How much do lawyers collect along the way?

And finally, is there an obligation to the blood descendants or should Hall's last wishes, as expressed in her will, be honored?

Sikes, a teacher of autistic children, says her mother received far less than six figures, and every penny of those royalties has gone to her care.

Sikes and LeBlanc say they still want to do something to honor Hall's memory, maybe placing a headstone on her grave, if they can find it, or organizing a blues festival in her honor.

''There are lots of things we would like to do. But at this point we haven't done anything,'' Sikes said.

EMAIL: tspencer@bhamnews.com

Comments

Post a Comment