North Alabama canyon almost untouched by time

|

| Photos by MATTHEW WILLIAMS |

Cane Creek preserve shelters rare plants

by THOMAS SPENCER

Birmingham News staff writer

Publication Date: April 29, 2007

TUSCUMBIA

As you enter the 413-acre Cane Creek Canyon Nature Preserve, you leave typical, rolling-hill Alabama farmland. A few minutes' walk from a farm pond in a grassy field, just past a freshly clear-cut forest tract, the woods thicken and the narrow stream you're following suddenly drops 60 feet in a dramatic waterfall.

It's the beginning of a canyon that cuts 350 feet deep into a plateau in the Little Mountains region of Colbert County. This cool, wet hideaway shelters the kind of forest that covered north Alabama during the Ice Age, 10,000 years ago.

The canyon, useless to farmers and difficult for loggers to cut, has stayed relatively intact, preserving rare plants and huge trees in a dramatic terrain. Thanks to Jim and Faye Lacefield, who have been buying up the land over the course of almost three decades, it will stay pristine as a place for researchers and people to come.

''We hope it will be a permanent preserve, open to the public,'' Jim Lacefield said.

The Lacefields bought the first 40 acres of the property in 1979.

Over time, they've invested about $180,000 drawn from an inheritance Jim received when his mother died and the sale of a house in Tampa that had appreciated in value. The Lacefields decided they wanted to do something with the money that wouldn't change their lifestyle, an investment that would be of lasting value for them and for others.

''The state can't buy all the land that you need to preserve,'' he said.

Standing under a sandstone overhang carved by the waterfall, Lacefield points to a delicate white flower called French's Shooting Star. This is the only place in Alabama the flower is known to grow. The nearest population is found 250 miles to the north. Farther back in the crevice is a filmy fern, also a rarity.

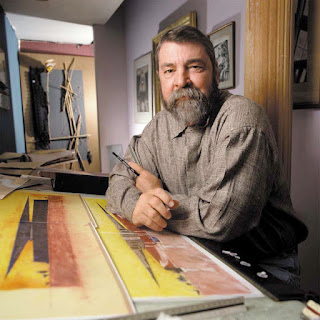

Lacefield is a semiretired geology and biology professor at the University of North Alabama and the author of ''Lost Worlds in Alabama Rock,'' a study of Alabama's geologic evolution through millions of years, its drift over the globe, the seas rising and falling, mountains soaring and crumbling.

Lacefield is a semiretired geology and biology professor at the University of North Alabama and the author of ''Lost Worlds in Alabama Rock,'' a study of Alabama's geologic evolution through millions of years, its drift over the globe, the seas rising and falling, mountains soaring and crumbling.On this April afternoon, Lacefield is hosting plant-loving visitors from Huntsville. He can read the rock, pointing out where a slant indicates an ancient ocean floor. He can point to different plant communities growing on the different layers exposed in the deepening canyon, plants that grow from sandstone, others from the limestone in the layer below and still others in the shale-dominated bottom.

Jerry Green of Huntsville had made the trip to shoot pictures of flowers in bloom. ''We just learn so much from Jim,'' he said.

And every time he visits he sees something new, Green said. In winter, with the trees stripped of leaves, the boulders and canyon cliff and overhangs are exposed. From spring through fall, a constant succession of flowers blooms. Varieties of trillium, mountain laurel, orchids, lilies, and a 5-foot-tall showy flower called the Columbo. There are medicinal plants such as mayapple, ginseng and gold seal.

''This is one of the places you have to come every two weeks,'' Green said.

Visitors are nothing new

People have been coming to this canyon for thousands of years. In the waning days of the last Ice Age, Paleo-Indians lived on the banks of the Tennessee River during summers and retreated to the rock overhangs in the canyon for shelter in the winter, when the river would swell with flooding rains. Archaeologists have dated charcoal from their fires to be among the oldest evidence of human habitation in Alabama.

Under the Lacefields' care, the land has become a destination for wildflower enthusiasts, photographers and researchers.

Don Farrar, an Iowa State University professor and an expert on filmy ferns, regularly brings graduate students to study specimens and habitat.

When a nationally known expert on ferns, Robbin Moran of the New York Botanical Garden, visited Birmingham's Botanical Gardens, his hosts took him on a field trip to the Lacefields'.

Rock climbers and Boy Scouts come to camp and climb. The Lacefields don't charge admission and are kind hosts.

Jim Lacefield, 59, grew up in Homewood and went to Shades Valley High School. He and Faye, who is also an educator, live on the land in a cozy Spanish mission-style home.

Not out to profit

Faye and Jim both spend considerable time hosting guests. They don't charge, don't sell timber off the land, and neither the Lacefields nor their children are expecting to reap a monetary windfall from the property today.

Alabama's low property taxes on forest land, $1 per acre per year, mean they don't have to spend a lot of money to keep the property. They are looking for a way to preserve the land permanently with perpetual care after they die. In the meantime, they live simply and get joy from sharing what they have.

From a bluff overlooking the main canyon, you can stand out on a huge boulder framed by windblown Virginia pines and look out six miles and not see another human habitation or road, just unbroken forest. ''It looks like a virtual wilderness,'' Lacefield said.

''This is a statement of our values,'' Lacefield wrote in an email, ''ones developed and internalized in times very different from the present, and perhaps quite different from those values promoted by society in general today. This is the best gift to the future that we can think of, and we do it without hesitation.''

EMAIL: tspencer@bhamnews.com

Comments

Post a Comment