|

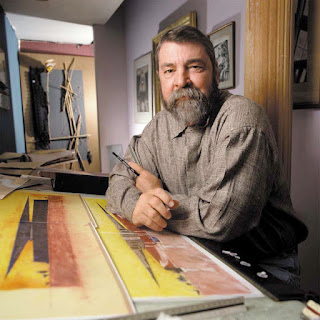

| Artis Wright of Rockford, Photo credit:Phillip Barr, The Birmingham News |

THOMAS SPENCER News staff writer

You have to love the thought of it.

Five hundred art patrons on a roadside in Pittsview, Alabama, a town that's not much more than a flashing yellow light south of Phenix City on U.S. 431. As trucks whiz by at 60 miles per hour, collectors from Atlanta peruse the latest offerings of housepaint-on-tin and scrap-metal-into-sculpture from local artists while they sip complementary Mad Dog 20/20 and nibble on hoop cheese and crackers.

Or maybe you're driving through Rockford, Ala., a slightly larger metropolis - one stoplight, population 500. On a bench on one side of the street is an 88-year-old retired roofing contractor in paint-speckled overalls, topped with a colorfully painted hat and backed by an array of brightly painted totems in the storefront behind him. Across the street, strumming on a blues guitar, his friendly rival, an artist and art dealer welcomes customers to his gallery full of fanciful folk art fish.

That's two art galleries in a four-block town, more galleries per block than New York City.

That's folk art. The craze over this primitive work has put Pittsville, Rockford and other obscure Alabama spots on the art world map.

The 20th Century Folk Art News calls folk art "art produced by untrained people who draw on their culture and experience in an isolated world. It is made with true, untutored, creative passion. It is raw, expressive, unconventional, non-conforming, genuine and truly original. Folk art should not be confused with country crafts, duck decoys or split cane baskets. It is highly personal art."

That makes Alabama an ideal home for a folk artist.

Our reputation as an uneducated backwoods is an asset, for once. People come to Alabama assuming that the state hatches folk artists like an old tire breeds mosquitoes. Creative, artistically inclined Alabamians, black and white, young and old, once considered just plain weird, are accorded Folk art, Page 8G 1G an almost reverential respect.

The artists being discovered in these small towns are not the few Alabama artists - Thornton Dial, Charlie Lucas, Moses Toliver, Lonnie Holley and Bill Traylor, to name a few - who've already been "discovered" and now are being taken seriously.

These artists are the secondstring folk team. Some may already be on their way to joining the elite. Others are just happy to be following their bliss.

And they aren't just waiting to be discovered by the outside art establishment and big galleries in Birmingham or Atlanta.

In remote places like Pittsview and Rockford, locally owned galleries are reaching an international audience via the Internet, selling local artists' works on personal Web sites or over the Internet auction site, eBay. Now self-taught Alabama artists who might otherwise have never sold a piece are making a living, meager though it may be.

But the folk art world is also a series of Catch-22s, traps for an artist. Artists can be taken advantage of or mistaken for a con artist. Sell too much and you've sold out. Remain obscure and starve. Hide any education you've got and play the stereotype, or risk losing your cachet.

In a world that is supposed to be innocent, raw and genuine, things can get complicated.

Even in Pittsview. Table uncovers talent

In 1994, James A. Buddy Snipes, then a 52-year-old lumber company worker, brought a creation into "Mayor" Frank Turner's antique shop.

Snipes traded with Turner on a regular basis, selling him old farm implements and furniture found in the surrounding countryside. But this piece, created by Snipes, was like nothing Turner had ever seen before: an upturned table top framed with mule plows, decorated with dirty, old snuff jars, and topped with a plastic chicken.

"I laughed out loud at the thing," Turner recalled.

Snipes remembers telling him, "That laugh is going to turn into a smile."

Turner did get a lot of smiles, paying $5 for the piece and putting it up for display in his antique shop with a $500 price tag.

Not long after, a group of Atlanta businessmen on a fishing trip stopped in the store. One took a picture of the objet d'art and soon after an Atlanta gallery owner traveled to Pittsview, in search of the local talent.

Thus encouraged, Snipes began to make more pieces, painting stick-figure portraits of relatives on old tin.

And they sold.

Snipes has the perfect folk art pedigree. A black man with almost no formal education, Snipes never had a bank account or driver's license before his folk art success. The money he's earned from his art has enabled him to buy a trailer where he now lives, though he still paints and creates in his former home, a shack with no running water, across the street, secluded in a grove of pines.

"I've been making things all my life," Snipes said on a recent afternoon, standing outside his workshop. "I was born with this gift."

On this afternoon, he is working on a wooden hat, which consists of a flat board cut into a circle with a beaver-tailed bill extending from it. The top of the board is painted and below is attached a circle of vertical sticks, bound by a copper wire, that surrounds the head.

"I love my work," Snipes said. "Whatever come into my mind, I got to do it."

He makes annual trips to Kentuck and other arts festivals and is called on, not infrequently, by art collectors and connoisseurs. He works full time as an artist.

"I'm doing pretty good," he said. "I'm the only one in the family that is famous. My neighbors they are shocked to death. They had no idea this was in me."

His success has, however, caused some friction on the Pittsview art scene.

Though Snipes doesn't have a formal education, he is business savvy. His relationship with Frank Turner, his original patron and booster, is strained.

Turner still buys and sells from Snipes, but their dealings are strict buy and sell deals. In the early days, Turner would give Snipes cash for his work and then turn around and sell them for whatever he could get for it. He kept track of the profits and passed the excess back to Snipes, Turner said. But as Snipes became more interested in the business side of things, disagreements about pricing and commissions arose. Turner admits that the floating nature of prices in the art market could lead to abuse. Folk art is supposed to be affordable so most artists in the category produce small pieces priced from $35 to $50. But bigger and more complex works can go for hundreds, even a thousand dollars. "It would be easy to take advantage of them," Turner said of his artists.

Yes, artists. After Snipes' work sold, other artists started bringing their work to Turner and gradually his antique shop metamorphosed into an art gallery.

"The Mayor's Office" is frequented not only by the casual Atlanta vacationer on the way to the beach, but also by more serious collectors. It has a Web site, an e-mail mailing list, and hosts, in March, the annual art show.

Turner, a retired school administrator, is not really the mayor of Pittsview, which is unincorporated. He's just the most recognizable character there.

Turner was a bit taken aback that people were paying serious attention to the humble creations of country folk. "It's sort of flabbergasting. I'd seen these things like bottle trees all my life," he said. "I didn't think anything of it. They were so common."

But Turner has come to admire their efforts. "You see what they have done with nothing." Finding a sign to create

Just up the road, a black laborer and farmer now in his 70s, John Henry Toney, was plowing one day then he turned up a turnip in which he saw the face of a man. This he interpreted as a sign that he was to create art.

Toney also lives in the perfect folk-art setting. At the far end of a dirt road, long poles propped on the ground hold closed the doors of his aged mobile home. He's surrounded by a quasimystical landscape: 10 remote acres populated with alligators in a swamp and panthers sighted by Toney, and a moon that follows him when he goes out at night.

Seated beneath a shade tree on a yard swept clean so the snakes stay away and talking above the din of cicadas, Toney explains his most recent work, a rendering of Adam and Eve, a bull and a snake. Adam is dressed like a cross between a jaunty cavalier and a gunslinger. Eve has an elaborate hair weave and large protruding bosoms, a recurring theme in Toney's work.

"She'll knock a man dead," he said.

Big breasts and hips catch men's eyes, he explained, and that's what sells.

Toney sketches with magic markers and commonly uses cut-up posterboard for a canvas. Toney's characters are of indeterminate-race people in a landscape shared with jet planes or dinosaurs in the plowing field.

Toney isn't quite sure what to make of the attention he's been getting. He suspects the visitors to his remote corner of the earth are looking for people pictured on wanted posters.

"As black as I am, you think they would come all the way from California to take a picture of me?" he asked.

Separating fact from fiction

Up the road in Seale at Butch Anthony's place, The Alabama Museum of Wonder, a braying jackass greets approaching cars and a brilliant blue and green peacock preens through a barnyard landscape cluttered with scrap metal sculpture.

Anthony, 36, is tall and lanky, always in overalls, his cap turned backwards. He is a softspoken P.T. Barnum, a slowdrawling country boy who is subtly hip to post-modern irony. He has a goofy grin and a disguised but formidable intellect. He's a carpenter, a welder and a gifted artifact hunter.

He lives in a large homemade log cabin built on the family farm and works in another log cabin he built when he was only 15.

He gave up his roadside barbecue restaurant for art, though he still works with his father, who conducts the Possum Trot Auction, where Butch buys a lot of his odd raw materials.

"His daddy is real nice, but he just shakes his head at this art," said Frank Turner.

Choosing just a few items to describe in Anthony's Museum of Wonder seems futile, but the converted maze-like barn includes real dinosaur fossils and Indian artifacts, a furless stuffed squirrel, several reconstituted crows and the cast of a Sasquatch footprint - faked but inspired by a local reported sighting.

There are several items on pseudo-museum display behind the glass of overturned mason jars: a foot-long nose hair from the Loch Ness Monster, a "crawball," a ball of string and twigs, fishing line and roots found in the craw of a chicken a local woman was dressing for a Sunday dinner, and the world's largest gallstone supposedly removed from a 487-pound woman from Albany, Ga.

Hanging in a far corner is a decorated gas mask billed as wreckage from an alien ship shot down over a Dothan dove.

What makes the whole journey through the Museum of Wonder particularly interesting is the impossibility of separating fact from fiction, from knowing whether Anthony is kidding or serious.

"How can you be serious about a space alien?" he laughed, when asked.

Through word of mouth, features on television and an extensive Internet operation, Anthony regularly receives visitors. Curious about the world but tied to his little corner of the earth, Anthony has found a way to bring the world to his door.

"You meet neat people from all over the world," he said.

He's made a serious a business out of being odd and designing humorous and pleasing painting and sculpture. "When I first started doing it, it was sort of a joke, but it got serious."

And he's also discovered a yearning to make art that will be taken seriously.

Trying to shed the folk art label, Anthony is the founder of the "Intertwangalism" movement. Intertwangalism takes a distinct way of expressing oneself (twang) and mixing it (inter) and making it, well, an "ism."

"Maybe we'll have our own thing going," Anthony says as he looks at one of his Picasso-like, Southern-fried nudes.

Meanwhile, he is having trouble with the powers-that-be, those who label art work. A visiting academic was charmed with Anthony's work until in the studio, he noticed Anthony's extensive library, which includes everything from Foxfire books and the complete works of Dr. Suess to biographies of Einstein and Jefferson and selections from Emerson and Thoreau.

"Look at all these books," the academic exclaimed.

"He got mad and left," Anthony said. "Some of those folklorists are crazier than the artists. They come studying us and somebody ought to be studying them, too." Avoiding perfection

Artis Wright, 88, Rockford, Alabama's original folk artist entrepreneur, knows how to meld his art to the expectations of the art world. He paints or builds what he sees in visions dancing on the ceiling at night. But he doesn't get it too right.

Folk art, he said, is art that "ain't made perfect."

"That's the reason I make one eye higher than the other or big eyes," he said.

If a piece is too symmetrical or realistic it won't sell. "The art people say it is too perfect," he said.

Wright lives in a house painted from ground to roof with Indians, warrior women, dogs and tigers. He uses turkey feet, cow bones and deer parts, fabric and paint to assemble sculptures and totems.

"I enjoy it and it helps me more than anything," he said. "I believe I would have been dead if I hadn't done it. My name is Artis and I reckon I was meant to be an artist."

He opened a shop on Rockford's main street about eight years ago, and now opens it up when he feels like it, mostly on Saturdays. He knows how to make a deal, as most folk artists do, protesting that he wouldn't sell this piece or that, playing his prices against the competition across the street.

"A little competition helps Rockford. It helps a lot to have two of them," Wright said.

Making it fun

Nor does Charlie Simpson mind the competition. A 48-year-old Brownsville, Texas, native, Simpson worked for Alabama Power and had a little real-estate company before he discovered he could make a living selling arts and crafts. He started with the crafts, making birdhouses from bark, poplar wood, and vines.

Then he discovered he had some talent with a paint brush. He put away his chainsaw, much to the relief of his wife, and began committing art.

"After building thousands of functional bird accessories, it was like somebody flung open the door and said have some light in your life," Simpson said.

A fisherman all his life, he liked doing wildly colored, cutout fish made of wood or license plates, 3-D birds, and hub caps turtles. Since his shop is near Lake Martin and the Coosa River, Simpson found his favorite subject was conveniently popular with his customers, but he's expanded beyond lake dwellers.

Mothers, he explained, like to decorate children's bedroom's with fish since they are genderneutral and nonviolent, he said.

"I also send a lot of stuff to the coast for condo decor," he said.

He also expanded his business to the Internet, selling from his own site and on eBay, the Internet auction site.

Last year, he was shipping three to five pieces a week sold over eBay to every state in the union. That market, though, is suffering from a glut and confusion.

His pieces on eBay are now lost among a huge swell of other artists selling their wares.

All of sudden, thousands of artists are calling themselves outside artists, some of whom, Simpson suspects, are disguising their formal art education and fictionalizing their biographies to fit the mold.

"Some of them look like someone has got his child chained to a tree painting angels," he said.

Unfortunately for Simpson, he has a little more education than the stereotype and lives modestly but comfortably. "I don't have a wooden leg, and I don't live in a trailer tottering on the edge of a cliff."

Still, the Web site is great exposure and his business is making enough to keep the lights on.

He has no delusions of grandeur. If an art shopper comes in looking for an art investment, he recommends other artists he stocks in the shop like Bernice Sims, an elderly black woman from Brewton whose work Simpson admires.

Forget the labels, Simpson recommends.

"Ideally, no one should categorize artists," he said.

Just buy what moves you.

"Folk art is supposed to be fun," he said.

Five hundred art patrons on a roadside in Pittsview, Alabama, a town that's not much more than a flashing yellow light south of Phenix City on U.S. 431. As trucks whiz by at 60 miles per hour, collectors from Atlanta peruse the latest offerings of housepaint-on-tin and scrap-metal-into-sculpture from local artists while they sip complementary Mad Dog 20/20 and nibble on hoop cheese and crackers.

Or maybe you're driving through Rockford, Ala., a slightly larger metropolis - one stoplight, population 500. On a bench on one side of the street is an 88-year-old retired roofing contractor in paint-speckled overalls, topped with a colorfully painted hat and backed by an array of brightly painted totems in the storefront behind him. Across the street, strumming on a blues guitar, his friendly rival, an artist and art dealer welcomes customers to his gallery full of fanciful folk art fish.

That's two art galleries in a four-block town, more galleries per block than New York City.

That's folk art. The craze over this primitive work has put Pittsville, Rockford and other obscure Alabama spots on the art world map.

The 20th Century Folk Art News calls folk art "art produced by untrained people who draw on their culture and experience in an isolated world. It is made with true, untutored, creative passion. It is raw, expressive, unconventional, non-conforming, genuine and truly original. Folk art should not be confused with country crafts, duck decoys or split cane baskets. It is highly personal art."

That makes Alabama an ideal home for a folk artist.

Our reputation as an uneducated backwoods is an asset, for once. People come to Alabama assuming that the state hatches folk artists like an old tire breeds mosquitoes. Creative, artistically inclined Alabamians, black and white, young and old, once considered just plain weird, are accorded Folk art, Page 8G 1G an almost reverential respect.

The artists being discovered in these small towns are not the few Alabama artists - Thornton Dial, Charlie Lucas, Moses Toliver, Lonnie Holley and Bill Traylor, to name a few - who've already been "discovered" and now are being taken seriously.

These artists are the secondstring folk team. Some may already be on their way to joining the elite. Others are just happy to be following their bliss.

And they aren't just waiting to be discovered by the outside art establishment and big galleries in Birmingham or Atlanta.

In remote places like Pittsview and Rockford, locally owned galleries are reaching an international audience via the Internet, selling local artists' works on personal Web sites or over the Internet auction site, eBay. Now self-taught Alabama artists who might otherwise have never sold a piece are making a living, meager though it may be.

But the folk art world is also a series of Catch-22s, traps for an artist. Artists can be taken advantage of or mistaken for a con artist. Sell too much and you've sold out. Remain obscure and starve. Hide any education you've got and play the stereotype, or risk losing your cachet.

In a world that is supposed to be innocent, raw and genuine, things can get complicated.

Even in Pittsview. Table uncovers talent

In 1994, James A. Buddy Snipes, then a 52-year-old lumber company worker, brought a creation into "Mayor" Frank Turner's antique shop.

Snipes traded with Turner on a regular basis, selling him old farm implements and furniture found in the surrounding countryside. But this piece, created by Snipes, was like nothing Turner had ever seen before: an upturned table top framed with mule plows, decorated with dirty, old snuff jars, and topped with a plastic chicken.

"I laughed out loud at the thing," Turner recalled.

Snipes remembers telling him, "That laugh is going to turn into a smile."

Turner did get a lot of smiles, paying $5 for the piece and putting it up for display in his antique shop with a $500 price tag.

Not long after, a group of Atlanta businessmen on a fishing trip stopped in the store. One took a picture of the objet d'art and soon after an Atlanta gallery owner traveled to Pittsview, in search of the local talent.

Thus encouraged, Snipes began to make more pieces, painting stick-figure portraits of relatives on old tin.

And they sold.

Snipes has the perfect folk art pedigree. A black man with almost no formal education, Snipes never had a bank account or driver's license before his folk art success. The money he's earned from his art has enabled him to buy a trailer where he now lives, though he still paints and creates in his former home, a shack with no running water, across the street, secluded in a grove of pines.

"I've been making things all my life," Snipes said on a recent afternoon, standing outside his workshop. "I was born with this gift."

On this afternoon, he is working on a wooden hat, which consists of a flat board cut into a circle with a beaver-tailed bill extending from it. The top of the board is painted and below is attached a circle of vertical sticks, bound by a copper wire, that surrounds the head.

"I love my work," Snipes said. "Whatever come into my mind, I got to do it."

He makes annual trips to Kentuck and other arts festivals and is called on, not infrequently, by art collectors and connoisseurs. He works full time as an artist.

"I'm doing pretty good," he said. "I'm the only one in the family that is famous. My neighbors they are shocked to death. They had no idea this was in me."

His success has, however, caused some friction on the Pittsview art scene.

Though Snipes doesn't have a formal education, he is business savvy. His relationship with Frank Turner, his original patron and booster, is strained.

Turner still buys and sells from Snipes, but their dealings are strict buy and sell deals. In the early days, Turner would give Snipes cash for his work and then turn around and sell them for whatever he could get for it. He kept track of the profits and passed the excess back to Snipes, Turner said. But as Snipes became more interested in the business side of things, disagreements about pricing and commissions arose. Turner admits that the floating nature of prices in the art market could lead to abuse. Folk art is supposed to be affordable so most artists in the category produce small pieces priced from $35 to $50. But bigger and more complex works can go for hundreds, even a thousand dollars. "It would be easy to take advantage of them," Turner said of his artists.

Yes, artists. After Snipes' work sold, other artists started bringing their work to Turner and gradually his antique shop metamorphosed into an art gallery.

"The Mayor's Office" is frequented not only by the casual Atlanta vacationer on the way to the beach, but also by more serious collectors. It has a Web site, an e-mail mailing list, and hosts, in March, the annual art show.

Turner, a retired school administrator, is not really the mayor of Pittsview, which is unincorporated. He's just the most recognizable character there.

Turner was a bit taken aback that people were paying serious attention to the humble creations of country folk. "It's sort of flabbergasting. I'd seen these things like bottle trees all my life," he said. "I didn't think anything of it. They were so common."

But Turner has come to admire their efforts. "You see what they have done with nothing." Finding a sign to create

Just up the road, a black laborer and farmer now in his 70s, John Henry Toney, was plowing one day then he turned up a turnip in which he saw the face of a man. This he interpreted as a sign that he was to create art.

Toney also lives in the perfect folk-art setting. At the far end of a dirt road, long poles propped on the ground hold closed the doors of his aged mobile home. He's surrounded by a quasimystical landscape: 10 remote acres populated with alligators in a swamp and panthers sighted by Toney, and a moon that follows him when he goes out at night.

Seated beneath a shade tree on a yard swept clean so the snakes stay away and talking above the din of cicadas, Toney explains his most recent work, a rendering of Adam and Eve, a bull and a snake. Adam is dressed like a cross between a jaunty cavalier and a gunslinger. Eve has an elaborate hair weave and large protruding bosoms, a recurring theme in Toney's work.

"She'll knock a man dead," he said.

Big breasts and hips catch men's eyes, he explained, and that's what sells.

Toney sketches with magic markers and commonly uses cut-up posterboard for a canvas. Toney's characters are of indeterminate-race people in a landscape shared with jet planes or dinosaurs in the plowing field.

Toney isn't quite sure what to make of the attention he's been getting. He suspects the visitors to his remote corner of the earth are looking for people pictured on wanted posters.

"As black as I am, you think they would come all the way from California to take a picture of me?" he asked.

Separating fact from fiction

Up the road in Seale at Butch Anthony's place, The Alabama Museum of Wonder, a braying jackass greets approaching cars and a brilliant blue and green peacock preens through a barnyard landscape cluttered with scrap metal sculpture.

Anthony, 36, is tall and lanky, always in overalls, his cap turned backwards. He is a softspoken P.T. Barnum, a slowdrawling country boy who is subtly hip to post-modern irony. He has a goofy grin and a disguised but formidable intellect. He's a carpenter, a welder and a gifted artifact hunter.

He lives in a large homemade log cabin built on the family farm and works in another log cabin he built when he was only 15.

He gave up his roadside barbecue restaurant for art, though he still works with his father, who conducts the Possum Trot Auction, where Butch buys a lot of his odd raw materials.

"His daddy is real nice, but he just shakes his head at this art," said Frank Turner.

Choosing just a few items to describe in Anthony's Museum of Wonder seems futile, but the converted maze-like barn includes real dinosaur fossils and Indian artifacts, a furless stuffed squirrel, several reconstituted crows and the cast of a Sasquatch footprint - faked but inspired by a local reported sighting.

There are several items on pseudo-museum display behind the glass of overturned mason jars: a foot-long nose hair from the Loch Ness Monster, a "crawball," a ball of string and twigs, fishing line and roots found in the craw of a chicken a local woman was dressing for a Sunday dinner, and the world's largest gallstone supposedly removed from a 487-pound woman from Albany, Ga.

Hanging in a far corner is a decorated gas mask billed as wreckage from an alien ship shot down over a Dothan dove.

What makes the whole journey through the Museum of Wonder particularly interesting is the impossibility of separating fact from fiction, from knowing whether Anthony is kidding or serious.

"How can you be serious about a space alien?" he laughed, when asked.

Through word of mouth, features on television and an extensive Internet operation, Anthony regularly receives visitors. Curious about the world but tied to his little corner of the earth, Anthony has found a way to bring the world to his door.

"You meet neat people from all over the world," he said.

He's made a serious a business out of being odd and designing humorous and pleasing painting and sculpture. "When I first started doing it, it was sort of a joke, but it got serious."

And he's also discovered a yearning to make art that will be taken seriously.

Trying to shed the folk art label, Anthony is the founder of the "Intertwangalism" movement. Intertwangalism takes a distinct way of expressing oneself (twang) and mixing it (inter) and making it, well, an "ism."

"Maybe we'll have our own thing going," Anthony says as he looks at one of his Picasso-like, Southern-fried nudes.

Meanwhile, he is having trouble with the powers-that-be, those who label art work. A visiting academic was charmed with Anthony's work until in the studio, he noticed Anthony's extensive library, which includes everything from Foxfire books and the complete works of Dr. Suess to biographies of Einstein and Jefferson and selections from Emerson and Thoreau.

"Look at all these books," the academic exclaimed.

"He got mad and left," Anthony said. "Some of those folklorists are crazier than the artists. They come studying us and somebody ought to be studying them, too." Avoiding perfection

Artis Wright, 88, Rockford, Alabama's original folk artist entrepreneur, knows how to meld his art to the expectations of the art world. He paints or builds what he sees in visions dancing on the ceiling at night. But he doesn't get it too right.

Folk art, he said, is art that "ain't made perfect."

"That's the reason I make one eye higher than the other or big eyes," he said.

If a piece is too symmetrical or realistic it won't sell. "The art people say it is too perfect," he said.

Wright lives in a house painted from ground to roof with Indians, warrior women, dogs and tigers. He uses turkey feet, cow bones and deer parts, fabric and paint to assemble sculptures and totems.

"I enjoy it and it helps me more than anything," he said. "I believe I would have been dead if I hadn't done it. My name is Artis and I reckon I was meant to be an artist."

He opened a shop on Rockford's main street about eight years ago, and now opens it up when he feels like it, mostly on Saturdays. He knows how to make a deal, as most folk artists do, protesting that he wouldn't sell this piece or that, playing his prices against the competition across the street.

"A little competition helps Rockford. It helps a lot to have two of them," Wright said.

Making it fun

Nor does Charlie Simpson mind the competition. A 48-year-old Brownsville, Texas, native, Simpson worked for Alabama Power and had a little real-estate company before he discovered he could make a living selling arts and crafts. He started with the crafts, making birdhouses from bark, poplar wood, and vines.

Then he discovered he had some talent with a paint brush. He put away his chainsaw, much to the relief of his wife, and began committing art.

"After building thousands of functional bird accessories, it was like somebody flung open the door and said have some light in your life," Simpson said.

A fisherman all his life, he liked doing wildly colored, cutout fish made of wood or license plates, 3-D birds, and hub caps turtles. Since his shop is near Lake Martin and the Coosa River, Simpson found his favorite subject was conveniently popular with his customers, but he's expanded beyond lake dwellers.

Mothers, he explained, like to decorate children's bedroom's with fish since they are genderneutral and nonviolent, he said.

"I also send a lot of stuff to the coast for condo decor," he said.

He also expanded his business to the Internet, selling from his own site and on eBay, the Internet auction site.

Last year, he was shipping three to five pieces a week sold over eBay to every state in the union. That market, though, is suffering from a glut and confusion.

His pieces on eBay are now lost among a huge swell of other artists selling their wares.

All of sudden, thousands of artists are calling themselves outside artists, some of whom, Simpson suspects, are disguising their formal art education and fictionalizing their biographies to fit the mold.

"Some of them look like someone has got his child chained to a tree painting angels," he said.

Unfortunately for Simpson, he has a little more education than the stereotype and lives modestly but comfortably. "I don't have a wooden leg, and I don't live in a trailer tottering on the edge of a cliff."

Still, the Web site is great exposure and his business is making enough to keep the lights on.

He has no delusions of grandeur. If an art shopper comes in looking for an art investment, he recommends other artists he stocks in the shop like Bernice Sims, an elderly black woman from Brewton whose work Simpson admires.

Forget the labels, Simpson recommends.

"Ideally, no one should categorize artists," he said.

Just buy what moves you.

"Folk art is supposed to be fun," he said.

If you want to purchase a scraper, we suggest that you go for one that's in one piece. best fish spatula

ReplyDelete