LESS REDNECK, MORE RIVIERA

BEACHFRONT DEVELOPMENT PUSHING OUT A WAY OF LIFE

BEACHFRONT DEVELOPMENT PUSHING OUT A WAY OF LIFETHOMAS SPENCER News staff writer

Publication Date: March 18, 2001

GULF SHORES A black stretch limousine turns onto the palm-lined drive and heads toward the spa, tennis courts and posh 20-story beachfront condos of the Beach Club Resort on Fort Morgan Road.

Across the street, looking forlorn and faded from the Gulf Coast sun, The General Lee, a genuine imitation souped-up Dukes of Hazzard Dodge Charger, sits with a "for sale" sign on the dash.

Across the street, looking forlorn and faded from the Gulf Coast sun, The General Lee, a genuine imitation souped-up Dukes of Hazzard Dodge Charger, sits with a "for sale" sign on the dash.The Fort Morgan peninsula, a narrow strip of land running west from Gulf Shores to the mouth of Mobile Bay, is the last bit of "country" on the Alabama Coast. But the same development pressures that transformed Orange Beach and Gulf Shores - now a long march of concrete condos with gates and guard shacks - is pushing out the Fort Morgan Road, the last miles of the untamed Alabama coast.

Property values are shooting up as golf resorts and Mediterranean-style garden homes replace scrub pines, sand dunes and weather-beaten beach homes. Environmentalists worry Riviera, Page 9A 1A about the damage to the fragile ecosystem.

But locals such as Sean Daw, owner of the aforementioned General Lee, worry that it's not just the endangered Alabama Beach Mouse that's losing its habitat.

"It used to be called the Redneck Riviera," Daw said, looking out from the porch of his bayside cabin at a yard full of vehicles that sit in various states of de- or reconstruction. "I'm out of place here now just about."

As spring break vacationers return to Orange Beach and Gulf Shores next weekend, the cropdusters will crank up to drone and drag their banners across the coastal sky. The fleets of rental Jet Skis will start their whine. The water slides will gush, the goofy golf balls will roll, the Ferris wheels will turn. Changing views

Far out on the Fort Morgan peninsula, you can still find the kind of place the entire Alabama Gulf Coast used to be: small cabins on stilts 20 miles from a grocery store; a place of plastictabled, non-arugula, fried seafood dives; a place that offers not much more than the basics of sun, sand, surf and lazy, nocares, no-rules, beer-drenched loafing.

This peninsula, too, is changing.

There's The Beach Club, which already has four skyscraping condo towers and plans two more 20-story Gulf front buildings. On the property next door, the Gulf Highlands project wants to put up four more towers similar in scale. Beyond the size of these developments is their Epicurean flavor. These are resorts, with fancy amenities. No shirt, no shoes, no service.

Firing up his Dodge, 21-yearold Daw, a self-described redneck, fishtails onto the Fort Morgan Road. With a gut-rumbling roar, he blows past the Beach Club and its Bass Ale-ontap-Asian-calamari-serving, highfalutin restaurant. In the sandy dust, he leaves its Frenchmanicure-Swedish-massage-spa, and he bears down on some slow-driving, wintering Midwestern snowbirds in a late-model Mercury.

"Right now, there are more of those down here than locals," Daw motions as he whips around and puts the pedal down.

For Daw, the L.A. (Lower Alabama) Coast is becoming a foreign land. Imagine, he says, strangers looking bewildered as his car, "the ultimate redneck vehicle," as he calls it, and asking, "What's the General Lee?" Or asking of the Rebel flag on the roof, "Is that the British flag?"

When he goes cruising on the Gulf Shores strip, he finds people cranking up hip-hop rhythms instead of Lynyrd Skynyrd. They're dressing like gangstas or GQ models. It's gotten so bad that the last time he sounded the General Lee's "Dixie" horn, he was pulled over and warned by the authorities that he had violated the noise ordinance.

"I guess rednecks aren't popular anymore," he says.

With 16 rods and reels rigged and ready to go, Daw still enjoys the simple pleasures of being able to fish in the waters right outside his back door, but he can't roam the dunes and the bay beaches as he once did.

"You wonder if somebody is going to yell at you for coming across their lawn," he says. "They're paving all the roads in Baldwin County. The whole atmosphere has changed."

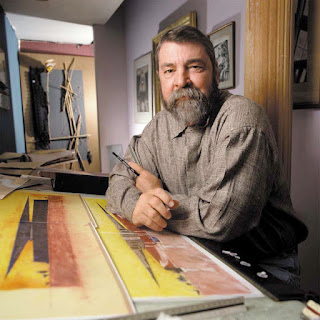

Harvey Jackson, a Jacksonville State University history professor, has frequented the Redneck Riviera since he was a teenager and has written about the changing face of the coast. As Jackson sees it, it's getting less Redneck and more Riviera.

"Somebody told me there is a place serving sushi down there, which is what we called 'bait' when I was growing up," Jackson said.

The transforming event for the Alabama Gulf Coast was 1979's Hurricane Frederic. The storm leveled many of the old beach shacks and budget hotels that dotted the coast, Jackson said. Developers snapped up the property and began building towering condos.

While the former generation of beach goers was content to get away from it all for a vacation, baby boomers are accustomed to more conveniences. They have more money to spend and demand more activity. The market is responding.

"These aren't people that are too inclined to redneck it up," Jackson said. "They don't want to drive 20 minutes to the store."

It's questionable whether the Fort Morgan Peninsula can handle the kind of all-out development that transformed Orange Beach and Gulf Shores.

It's questionable whether the Fort Morgan Peninsula can handle the kind of all-out development that transformed Orange Beach and Gulf Shores.More than half the Fort Morgan Peninsula is in the hands of the federal and state governments, including vast wildlife preserves and the site of Fort Morgan itself, the fort that protected Mobile Bay in the Civil War and is now a state museum. Locals concerned

Local residents are already concerned that with the developments on the drawing board, evacuation in the event of a hurricane could be a mess.

Russ and Tami Woerner, the owners of the Fort Morgan Marina, near the peninsula's tip, have discovered that nature's hand is keeping them from overbuilding. They've tried dredging the channel to the marina so it could accommodate bigger boats, but the currents fill it in before the year is up. In the seven years they've owned the marina, three hurricanes have damaged their business.

It hasn't stopped them from trying. With a condo development going up across the road, the Woerners are building a massive dry-dock, 140-boat storage facility.

Jackie Lee, who co-owns the restaurant and bar at the marina and runs a charter fishing boat, said he moved to Fort Morgan from his Cullman County chicken farm because he likes the peninsula's rural atmosphere.

"I hate to see it change, but this is going to see it happen," he said. Of course, for him, it has meant a doubling of his charter boat business, and the restaurant stays busy with construction workers in the winter and tourists in the summer.

And his clientele is changing, he said. "We're getting more money people."

At least for now, it hasn't caused him to change much. At his Happy Hooker Beach Bar, construction workers and chicken farmers mingle with doctors, lawyers and judges. They all sing karaoke when it gets late enough. "Seems like when they get out here, everybody is the same," he said.

He did replace the wirescreen windows with glass, but it is still dim inside. The floors are uneven. The plywood walls and the rough-beam rafters and posts are decorated with curling Polaroids. The outdoor patio tables are emptied wire spools, and people still drink beer sitting there, with their feet in the sand, the smell of fish from the boats returned to the docks, the sun setting on Mobile Bay.

"People want it to stay like it is," Lee said.

Comments

Post a Comment